How Is Research Inside Pacific’s Green Labs & Centers Evolving to Be More Sustainable?

By: Anita Li

The Carlson Lab in the Chemistry Department conducts research on natural microbes under the direction of Dr. Skylar Carlson, a pharmacognosist and professor at University of the Pacific. Image courtesy of Anita Li, Pacific Sustainability 2025.

At University of the Pacific, research labs and centers are where innovative ideas take shape from petri dishes, field sites, survey datasets, and rooms lined with glassware humming in the background. From chemistry to environmental economics and policy, faculty and students are formulating questions and answering them through amazing discoveries in the realms of health, climate, and community with an impact that stretches far beyond the Pacific Stockton campus. But how are these labs at Pacific answering this question as the age of sustainable innovation at the University also grows: What does it mean to do research sustainably?

On the Stockton campus, the shift toward “green labs” is evolving from a buzzword into meaningful action. It is changing how researchers think about water use, energy consumption, waste streams, travel, and even the way their findings are shared. Green labs aim to make scientific research more sustainable by reducing waste, conserving resources, and choosing smarter, low-impact methods. But how are they approaching this?

Reimagining Microbes and Waste

DI water production and capture system used in The Carlson Lab. Image courtesy of Anita Li, Pacific Sustainability 2025.

In the Chemistry department, pharmacognosist Dr. Skylar Carlson searches for new drugs in some of the oldest places on Earth: soil and the microbes that live within it. “My lab looks for new drugs from nature,” she explains. “We use microbes as our little chemical factories. They are the ones making the small molecules we isolate.” That ecological focus extends to how her lab operates.

Producing deionized water (DI water), essential for most experiments which typically wastes nearly twice as much water as it produces. Rather than letting that water flow wastefully down the drain, Carlson’s lab captures and reuses it in autoclaves and other systems that do not require ultrapure water. Dr. Carlson also clarifies that this water can be used to water plants too.

The lab also takes aim at plastic and chemical waste. Students intentionally design experiments that minimize pipette-tip use, choose greener solvents where possible, and recycle those solvents using low-pressure evaporation systems. Furthermore, waste is mindfully sorted into three streams: household-type waste, lab-specific plastics, and biohazards decontaminated in the autoclave instead of utilizing bleach. Autoclaves are also used in the lab, a process for sterilization for research instruments and equipment at high heat and pressure.

Energy use also comes under scrutiny. Ultra-low-temperature freezers, which house years’ worth of research, run constantly. Upgrading to more efficient models has earned the University rebates while reducing long-term electricity demand. The freezer is shared, storing boxes instead of filling them with mostly empty personal containers. “We don’t have unlimited financial resources or unlimited planetary resources,” Carlson said. “So we try to be mindful about what we order, how we use it, and how we dispose of it.”

Balancing Sterility and Sustainability

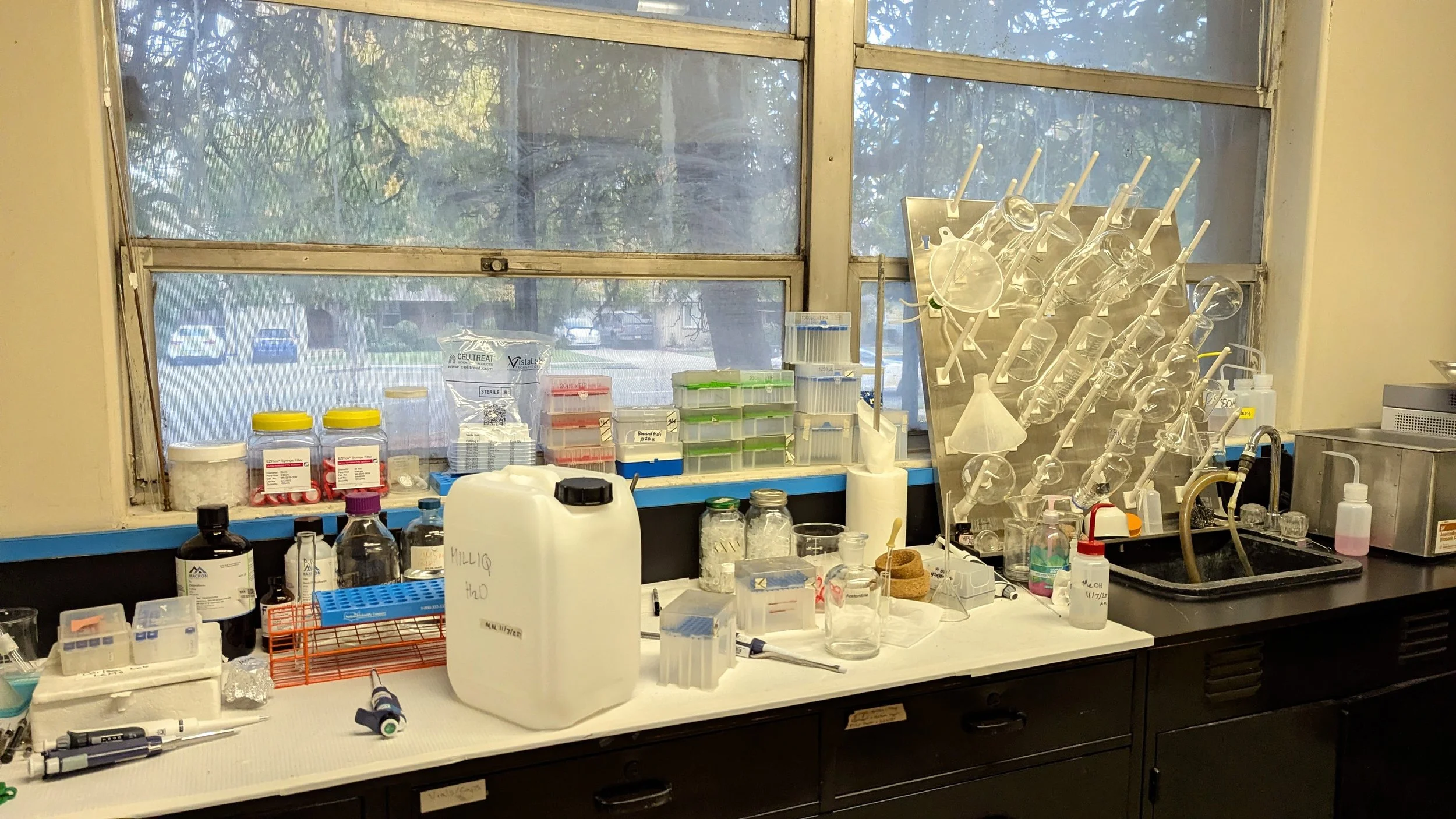

A laboratory bench featuring beakers, pipettes, and a glassware drying rack used for ongoing research activities. Image courtesy of Anita Li, Pacific Sustainability 2025.

From the Biology Department, lab managers like Kenneth Nguyen, oversee laboratory stock for both labs and courses that include a lab section. Sustainability often meets its toughest challenge: sterility.

“On one hand, we value sterility and consistency,” he said. “But on the other hand, we must be accountable for our effects on the environment.” Some procedures require unavoidable single-use plastics such as pipette tips, microtubes and culture plates. These often cannot be reused or recycled due to contamination risks. To counterbalance what can not be changed, the Biology Department has turned to refurbished and rescued inventory: unopened pipettes past their formal testing date, refurbished pipette controllers, and bulk supplies acquired to reduce packaging and cost.

The challenge lies in balancing research needs with environmentally conscious practices. Even where plastics cannot be reduced, procurement choices can meaningfully cut waste and save money.

Green Lab Thinking Beyond Laboratories

Not every lab at University of the Pacific uses chemicals or centrifuges. In the Economics Department, Dr. Samrat B. Kunwar leads research teams focused on climate resilience, water, equity, and environmental policy — work that is human-centered rather than equipment-intensive.

“The work my team does is mostly focus groups, surveys, and data analysis,” Kunwar said. “But sustainability still shows up in how we design and carry out our research.” Kunwar’s current project examines how residents in San Joaquin County value different carbon-removal strategies, from soil carbon storage to industrial techniques. His team intentionally minimizes its footprint through various methods, including:

Local-first fieldwork: Interviews and focus groups are held in community spaces, on nearby farms, and at partner organizations by limiting travel, keeping the benefits of research within the region.

Reducing “policy waste”: The data they produce is designed for immediate use by local governments and nonprofits by reducing repetitive, duplicative studies and accelerating action.

Building a sustainable workforce: Students learn to work with environmental data, conduct field research, and analyze policy questions. This builds local capacity for emerging climate-related careers in the Central Valley.

“Pacific has a real advantage because our size encourages collaboration across disciplines,” Kunwar states. “Our labs and research centers act as bridges between environmental research, policy, and community well-being.”

A Regional Ecosystem of Innovation

University of the Pacific’s three campuses, Stockton, San Francisco, and Sacramento, form a unique triangle of industry, health, and policy. This geography creates a natural network where environmental science, communication, business, dentistry, and public policy can collaborate in ways most universities cannot. Dr. Thomas Pogue, Executive Director of the Center for Business and Policy Research (CBPR) explained that Pacific’s regional presence allows the University to stay connected to innovation and funding in the Bay Area while testing and scaling ideas in the Central Valley, where there is space and infrastructure to implement them.

At CBPR, Dr. Thomas Pogue, Steven McCarty, and the CBPR student team have transitioned from printed reports to digital dashboards and online publications. This shift has reduced paper use while expanding public access to regional economic data. Dr. Pogue noted that although moving online minimizes printing and mailing, digital platforms introduce their own sustainability considerations, including long-term data storage and energy use.

CBPR also sees a major opportunity in clean technology. Many emerging innovations, such as building materials made from agricultural byproducts like walnut shells, would require real-world testing space and manufacturing capacity. He emphasized that while Bay Area companies often generate ideas, the Central Valley offers manufacturing space, logistics infrastructure, and labor readiness that can help bring those ideas to market.

For Dr. Thomas Pogue, his purpose at the CBPR is beyond data graphs; it is regional transformation. He emphasized that reframing sustainability as an economic growth strategy can open new pathways for innovation and investment, positioning the University within the region’s expanding clean-energy ecosystem.

What emerges is a broader concept of a “green lab” being more than just a room with equipment, but an entire ecosystem of collaboration, linking local knowledge, policy, infrastructure, and innovation. To learn more about CBPR’s research analyses in the categories of business, economics, and public policy, visit their website.

Knowledge Is Power

Pacific offers an interdisciplinary major and minor in sustainability. Courses such as Environmental Economics (ECON 157) introduce students to environmental justice mapping tools, policy tradeoffs, and climate-related economic impacts.

For those hoping to take part in these initiatives through research or want to learn more, Pacific faculty offer thoughtful guidance. “You don’t need to think of yourself as ‘an environmental person’ to contribute,” Kunwar explains. “If you care about public health, air quality, groundwater, inequality, housing – these are all threads of the same tapestry.”

Dr. Carlson also recommends students to request permission to shadow at labs they are interested in. Her website The Carlson Lab, also has many wonderful resources for students interested in research and possibly pursuing graduate school. She also mentioned to ask questions on whatever students are wondering.

A Greener Campus, One Decision at a Time

University of the Pacific Burns Tower in the center, framed with tree foliage. Image courtesy of Anita Li, Pacific Sustainability 2025.

None of Pacific’s labs claim to have solved the sustainability puzzle. There are definitely still steps that can be taken towards an even more sustainable approach. Although cost is a factor, with future advancements in research, there is hope for a day when sustainability methods are more cost-efficient compared to single-use alternatives. And yet, across the University, small decisions are accumulating.

At Pacific, “green research labs” and “green research centers” are not a separate initiative pushed from above. They are becoming part of the everyday culture of research, and in the academic space, a set of choices is made by faculty, students, and staff who view sustainability not as an obstacle, but as an opportunity to engage in innovation. The future of research depends not only on the discoveries made, but also on how they are made, and whether that process protects the communities and environments that research is meant to serve.

Inspired by the article? Want to be a part of a physical research lab or build even more sustainable labs? Contact SustainingPacific@PACIFIC.EDU, to receive information about being part of “my green labs” and green labs info session!